I'm not sure what little voice told me to go back out to the greenhouse late on the afternoon of November 29. I didn't have any particular mission there. I'd watered that morning. I just wanted to go back out. As I opened the sliding door to the little patio, there was a squeak and a flutter, and a tufted titmouse sort of trundled out of a pile of sycamore leaves that had blown up against the house. Dark was coming on, and I figure it had been planning to roost there. Oh dear! No titmouse in its right mind roosts on the ground, unless it has no other choice. This one was fluttering in a tight circle, its head tilted far over to the side. Something bad had happened to it. What were the chances it would fetch up against the very door I use the most? Was it chance, or something else? Birds know. They know.

I fetched my butterfly net and dropped it over the little bird. It was in a bad way. I put it in a plastic Critter Keeper and pulled back to observe it. Tipping over on its side, it was stargazing, with an inverted head. Uh-oh. That looked like traumatic brain injury to me. Whatever had happened to it, it would need food, so I prepared a little dish of Zick Dough and crushed sunflower hearts. The poor bird began to eat before I could even withdraw my hand, something that I would learn is typical of titmice. They are survivors, fighters. It took a sunflower heart, tried to tuck it in its toes, but couldn't get its head to cooperate, so it dug into the Zick Dough. I was so touched by its will to live that I pledged on the spot to do whatever it took to get it back into the wild. And if it wasn't going to make it, at least it would have had a warm place to sleep, and a full belly before it died.

The Intake Video...I had a feeling it wasn't going to die! But neither was I prepared for what happened next.

From the get-go, I got a strong male energy from this bird, so I'm going to switch its pronouns to he/his. Some may laugh at me. They may go ahead. So far, I've batted 100, even with sexually monomorphic birds like brown thrashers, song sparrows, and blue jays. We raised three brown thrasher nestlings a few years back. By the first evening I knew I had two females and a male. Harper, Melba and Cletus. And who first found his voice on June 22? Cletus. And the other two remained silent. Same with the three song sparrows I just raised. Two males and a female. Ball, Bob and Baby, the only female. I just knew.

Cletus sings quietly, June 22, 2015, on his 37th day of life.The sight that greeted me the next morning, after this promising beginning, was shocking. The poor titmouse's head was completely inverted, and any attempt at moving caused him to flip over on his back. Holding the bird up to the light, I could see its left eye flicking back and forth, a condition called nystagmus. I've had it with the three cases of vertigo I've endured, and it is no fun at all. The world spins around you and all you can do is close your eyes and try not to throw up.

Shila pointed out to me that the day or two after a car accident are usually worse than the day of the accident, as the body assesses what just happened to it. So it was for this bird. Though titmice are savvy birds and not typically victims of window strikes, one could surmise that perhaps a raptor had made a pass through the yard and scared him into a window collision. Brain swelling could easily cause the torticollis and nystagmus. I wanted to alleviate that, so as soon as offices opened at 8 I started calling around to locate Metacam, an NSAID that veterinarians use for brain trauma. It's what they give window-struck birds that squads of volunteers collect in the streets of big cities during migration. I'm grateful for the local veterinarian who is willing to sell me the drugs I need!

By 10 AM, I had charged to town, grabbed the meds, bought a flame-orange reflective dog collar, picked out and tied a Christmas tree on top of the car, and had the first dose of Metacam in the titmouse. Still Nov. 30 was rough. I had to hand-feed the bird hourly from dawn to dark. And he looked so pathetic, all twisted up and unable to move, that it was hard not to lose hope. And hard not to wonder how long we'd have to keep this up.

I had good reason to wonder. I remembered a case like this from way back in my Connecticut life, a bird named Sunshine.

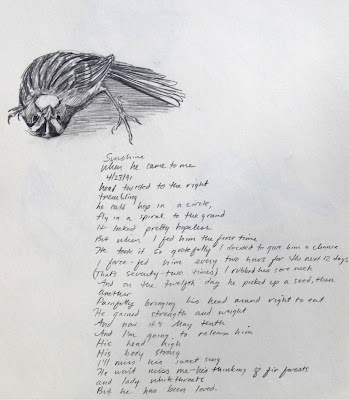

He was a white-throated sparrow, named by the little daughters of the woman who'd picked him up, and he had severe torticollis. I wouldn't discover the cause for several days: a deep wound right at the base of his skull, likely inflicted by a cat. I guess that qualifies as a traumatic brain injury! I got him on April 23, 1991, and it took twelve days of hourly hand-feeding and physical therapy (gently turning his head the way it didn't want to go) until the bird could self- feed again. By the 19th day, he was ready for release. Against all odds, I had a viable, releasable white-throated sparrow where once there was a sad little lump of feathers with an upside-down head.

Click on the picture to read his story.

Based on that experience, which was both grueling and transformative, I had reason to be hopeful about this titmouse. I was unshakably determined to see him through to whatever outcome Fate would decree.

3 comments:

You are the role model of compassion and caregiving. Thank you for all that you do, Julie. I send good wishes to you and that Titmouse. Hoping all goes well there.

I am awestruck by your care for nature, Julie. Your care for all of God's creatures is heroic.

Please let us know the outcome, whatever it is! I am hopeful for theis titmouse!

(And thank you for enabling comments for those of us who don't have a Google account -- and don't want one!)

Post a Comment